With a nod to the Harper’s Index, here’s the Meatonomics version of 40 numbers that tell a story. Sources for all figures are cited below. To view or download as a pdf, click here.

Average market value of a cow in the North Central United States : $245

Average cost to raise a cow in that region : $498

Amount US taxpayers spend yearly to subsidize meat and dairy : $38 billion

To subsidize fruits and vegetables : $17 million

US retail price of a pound of chicken in 1935 (adjusted for inflation) : $5.07

In 2011 : $1.34

Pounds of chicken eaten annually per American in 1935 : 9

In 2011 : 56

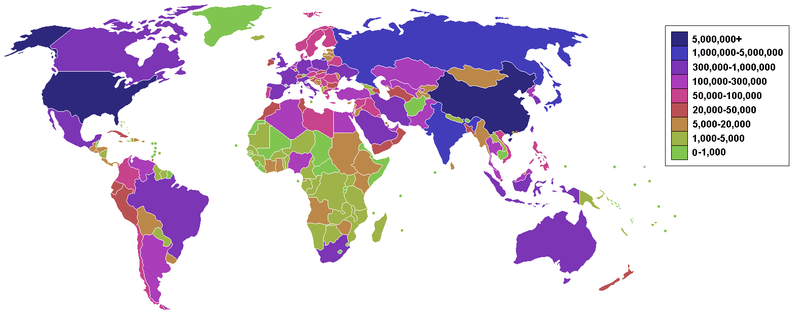

Factor by which US per-capita consumption of chicken and other meat exceeds world average : 3

By which US incidence of cancer exceeds world average : 3

Portion of US cancer, diabetes and heart disease cases related to meat and dairy consumption : 1/3

Annual cost to treat US cases of these diseases related to meat and dairy consumption : $314 billion

Portion of annual Medicare spending this represents : 3/5

Dietary cholesterol needed by humans, per National Academies’ Institute of Medicine : 0

Daily maximum recommended dietary cholesterol, per USDA (in milligrams) : 300

Milligrams of cholesterol per gram of ground beef : 0.9

Per gram of salmon : 0.9

Revenue collected by US fishing industry per pound of fish caught : $0.59

Portion of this figure funded by taxpayers as subsidies : $0.28

Pounds of dead fish and other animals discarded daily as unintended “bycatch” : 200 million

Portion of the worldwide targeted catch this represents : 2/5

Portion of Earth’s wild fisheries that have collapsed and ceased producing : 1/3

Pounds of wild fish needed to raise one pound of farmed salmon or tuna : 5

Portion of US seafood that comes from fish farms : 1/2

Number of foot-long, farmed trout typically raised in a space the size of a bathtub : 27

Number of pain receptors on the face and head of a trout : 18

Average amount Americans would pay to end inhumane hyper-confinement of pigs : $345

Number of states whose animal cruelty laws do not protect farmed animals : 37

Number of federal anti-cruelty laws that protect farmed animals during their lifetimes : 0

Annual government-managed “checkoff” spending to promote meat and dairy : $557 million

To promote fruits and vegetables : $51 million

Grams of protein in three ounces of canned ham : 18

In three ounces of roasted pumpkin seeds : 27

Average percentage by which a vegan’s blood cholesterol level is lower than an omnivore’s : 25

By which her weight is lower : 18

By which her life expectancy is longer : 13

Human lives that a 50% excise tax on meat and dairy would save yearly : 172,000

Animal lives it would save : 26 billion

Pounds this tax would cut yearly from US carbon-equivalent emissions : 3.4 trillion

Pounds of carbon equivalents emitted yearly from all US motor vehicles and vessels : 3.3 trillion

SOURCES

Note: The sources below provide raw data. For full explanations and detailed calculations, see David Robinson Simon, Meatonomics: How the Rigged Economics of Meat and Dairy Make You Consume Too Much—and How to Eat Better, Live Longer, and Spend Smarter (San Francisco: Conari Press, 2013).

Value and cost of a cow: Sara D. Short, “Characteristics and Production Costs of US Cow-Calf Operations,” USDA Statistical Bulletin 17, no. No. 947-3 (2001) (data for “North Central” region).

Subsidies to meat and dairy: Grey, Clark, Shih and Associates, Limited, “Farming the Mailbox: US Federal and State Subsidies to Agriculture – Study Prepared for Dairy Farmers of Canada” (2010); U. Rashid Sumaila et al., “A Bottom-Up Re-Estimation of Global Fisheries Subsidies,” Journal of Bioeconomics 12 (2010): 201–225; Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), “Agriculture and Health Policies in Conflict” (2011).

Subsidies to fruits and vegetables: Iowa Public Interest Research Group, “Junk Food Trumps Fruits and Vegetables in Federal Subsidies,” EcoWatch.

Chicken prices and consumption: US Census Bureau, Statistical Abtracts (1940); US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Average Prices (2011)”; USDA Economic Research Service, “Red Meat and Poultry – Per Capita Availability.”

Per capita meat consumption and cancer incidence by country: ChartsBin, http://chartsbin.com; World Cancer Research Fund International, “Data Comparing More and Less Developed Countries”; American Cancer Society, “Cancer Facts and Figures 2011”; National Cancer Institute, “Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results.”

Disease cases related to meat and dairy consumption: Romaina Iqbal, Sonia Anand, and Stephanie Ounpuu, “Dietary Patterns and the Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction in 52 Countries: Results of the INTERHEART Study,” Circulation 118, no. (19) (2008): 1929–-37; A. R. P. Walker, “Diet in the Prevention of Cancer: What Are the Chances of Avoidance?” The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 116, no. 6 (1996): 360–66; Dariush Mozaffarian et al., “Lifestyle Risk Factors and New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus in Older Adults,” Archives of Internal Medicine 169, no. 8 (2009): 798–807.

Costs to treat diseases related to meat and dairy consumption: Paul A. Heidenreich et al., “Forecasting the Future of Cardiovascular Disease in the United States: A Policy Statement from the American Heart Association,” Circulation 123 (2011) 933–-944; American Cancer Society, “Cancer Facts & Figures 2012”; American Diabetes Association, “Economic Costs of Diabetes in the US in 2007,” Diabetes Care 31, no. 3 (2008); US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Diabetes – Success and Opportunities for Population-Based Prevention and Control: At a Glance 2010.”

Medicare spending: US Department of Health and Human Services, “2014 Budget.”

Cholesterol needed and recommended: National Academy of Sciences, Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2005); USDA, “Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010.”

Cholesterol in ground beef and salmon: USDA, “Cholesterol (mg) Content of Selected Foods per Common Measure, Sorted by Nutrient Content,” National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 21 (2008).

Fishing revenue and subsidies: U. Rashid Sumaila et al., “A Bottom-Up Re-Estimation of Global Fisheries Subsidies,” Journal of Bioeconomics 12 (2010): 201–225; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “US Domestic Seafood Landings and Values Increase in 2010” (2011).

Bycatch: R. W. D. Davies et al., “Defining and Estimating Global Marine Fisheries Bycatch,” Marine Policy 33, no. 4 (2009): 661–72; Michael Parfit, “Diminishing Returns,” National Geographic (November 1995).

Collapse of fisheries: Boris Worm, et al., “Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services,” Science 314, no.: 5800 (2006): 787–-90.

Wild fish fed to farmed fish: Rosamond L. Naylor et al., “Effect of Aquaculture on World Fish Supplies,” Nature 405 (2000): 1017–24.

Farmed fish consumption: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “Fishwatch: US Seafood Facts.”

Trout stocking density and pain receptors: Matthias Halwart, Doris Soto, and J. Richard Arthur, eds., Cage Aquaculture: Regional Reviews and Global Overview (technical paper no. 498, UN FAO Fisheries, Rome, 2007); Lynne U. Sneddon, Victoria A. Braithwaite, and Michael J. Gentle, “Do Fishes Have Nociceptors? Evidence for the Evolution of a Vertebrate Sensory System,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 270, no. 1520 (2003): 1115–21.

Willingness to pay to end animal cruelty: F. Bailey Norwood and Jayson L. Lusk, Compassion by the Pound: The Economics of Farm Animal Welfare (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 344–45.

Anti-cruelty laws: Cody Carlson, “How State Ag-gag Laws Could Stop Animal-Cruelty Whistleblowers,” The Atlantic (March 25, 2013).

Checkoff spending: Geoffrey S. Becker, “Federal Farm Promotion (‘Check-Off’) Programs,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress (2008) (figure for fruits and vegetables excludes soybeans and sorghum, most of which are fed to farmed animals).

Protein in ham and pumpkin seeds: USDA, “Content of Selected Protein (g) Foods per Common Measure, Sorted Alphabetically,” National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 24.

Cholesterol, weight and longevity advantages of vegans: Jack Norris and Ginny Messina, “Disease Markers of Vegetarians” (2009), accessed August 19, 2012, http://www.veganhealth.org (referenced data are from table 1, “Cholesterol in USA Vegans”); S. Tonstad et al., “Type of Vegetarian Diet, Body Weight, and Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes,” Diabetes Care 32, no. 5 (2009): 791–96; Gary E. Fraser and David J. Shavlik, “Ten Years of Life – Is It a Matter of Choice?,” Archives of Internal Medicine 161 (2001); US Census Bureau, “Expectation of Life at Birth, and Projections” (2012).

Lives saved by meat tax: humans – “Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2009,” US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Vital Statistics Reports 59, no. 4 (2011) (assumes 44.1% reduction in consumption and corresponding reduction in deaths related to meat and dairy consumption; for details see Simon, Meatonomics); animals – Free from Harm, “59 Billion Land and Sea Animals Killed for Food in the US in 2009” (2011), accessed August 18, 2012, http://freefromharm.org (assumes 44.1% reduction in consumption).

Carbon equivalent emissions saved by meat tax: According to the US EPA, total US carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent emissions were 6,821.8 million metric tons (MMT) in 2010. (US EPA, “US Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report,” Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2010 (2012). Researchers estimate that 51% of emissions of CO2 equivalents is attributable to animal agriculture, which represents 3,479.1 MMT of the US total. (Robert Goodland and Jeff Anhang, “Livestock and Climate Change: What if the Key Actors in Climate Change Are . . . Cows, Pigs and Chickens?” World Watch (November/December 2009.) The 44.1% of this figure that the tax proposal would eliminate is 1,534 MMT, or 3.4 trillion pounds of CO2 equivalents. That is more than the 1,497 MMT that the US EPA estimates was emitted in 2010 by all US motor vehicles and vessels. (US EPA, “Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” 14, table 3.12; note that MMT and teragrams are equivalent units of measure.)