Are you being manipulated into buying things you don’t want or need? In my book Meatonomics, I show that animal food producers control our everyday food-buying choices with misleading messaging, artificially low prices, and heavy control over legislation and regulation. This producer behavior is simply shocking. The result is that in many respects, we have lost the ability to decide for ourselves what – and how much – to eat.

By learning just 10 quick facts about this industry and its highly coordinated messaging and manipulation, you can empower yourself to make better-informed choices immediately. You’ll see benefits to your health, your waistline, your ecological footprint, and more.

1. In a creepy, Big-Brotherish tactic straight out of a sci-fi movie, the federal government uses catchy slogans to get people to buy more meat and dairy.

Beef. It’s what’s for dinner.

Beef. It’s what’s for dinner.

Milk. It does a body good.

Each year, USDA-managed programs spend $550 million to bombard Americans with slogans like these urging us to buy more animal foods. Although people in every age group already eat more animal protein than recommended, and far more than our forebears did, these promotional programs are shockingly effective at making us buy even more. Each marketing buck spent boosts sales by an average of $8, for an annual total of an extra $4.6 billion in government-backed sales of meat, dairy, and eggs.

2. Americans eat more meat per person than any other people on earth, and we’re paying the price in doctor bills.

At 200 pounds of meat per person per year, our high meat consumption is hurting our national health. Hundreds of clinical studies in the past several decades show that consumption of meat and dairy, especially at the high levels seen in this country, can cause cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and a host of other diseases. Thus, Americans have twice the obesity rate, twice the diabetes rate, and nearly three times the cancer rate as the rest of the world. Eating loads of meat isn’t the only reason people develop these diseases, but it’s a major factor.

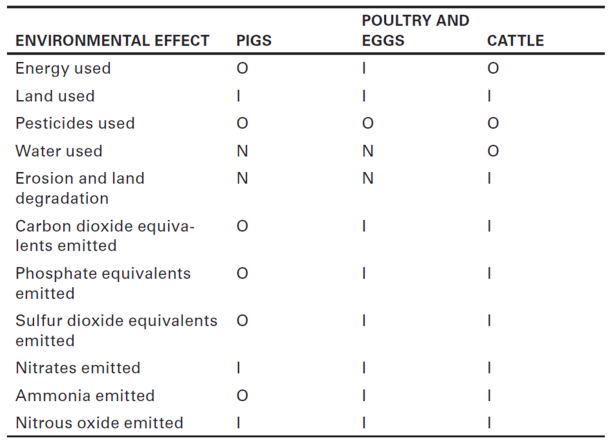

3. Animal food production is the world’s leading cause of climate change.

That’s right. Forget carbon-belching buses or power plants. Animal food production now surpasses both the transportation industry and electricity generation as the greatest source of greenhouse gases. Yet amazingly, if Americans could just cut back on animal foods by half, the effect on greenhouse gas emissions would be like garaging all U.S. motor vehicles and vessels for as long as we keep our consumption down.

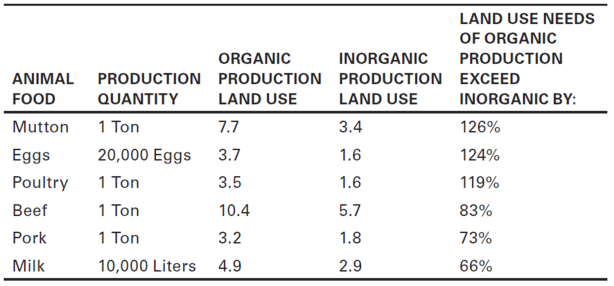

4. There’s no sustainable way to raise animal foods to meet the world’s growing demand.

Two acres of rain forest are cleared each minute to raise cattle or crops to feed them. 35,000 miles of American rivers are polluted with animal waste. We’re watching a real-time, head-on collision between the world’s huge demand for animal foods and the reality of scarce resources. It takes dozens of times more water and five times more land to produce animal protein than equal amounts of plant protein. Unfortunately, even “green” alternatives like raising animals locally, organically, or on pastures can’t overcome the basic math: the resources just don’t exist to keep feeding the world animal foods at the level it wants.

5. A $5 Big Mac would cost $13 if the retail price included hidden expenses that meat producers offload onto society.

Animal food producers impose $414 billion in hidden costs on American society yearly. These are the bills for healthcare, subsidies, environmental damage, and other items related to producing and consuming meat and dairy. That means that each time McDonald’s sells a Big Mac, the rest of us pay $8 in hidden costs.

Animal food producers impose $414 billion in hidden costs on American society yearly. These are the bills for healthcare, subsidies, environmental damage, and other items related to producing and consuming meat and dairy. That means that each time McDonald’s sells a Big Mac, the rest of us pay $8 in hidden costs.

6. American governments spend $38 billion each year to subsidize meat and dairy, but only 0.04% of that ($17 million) to subsidize fruits and vegetables.

The federal government’s Dietary Guidelines urge us to eat more fruits and vegetables and less cholesterol-rich food (that is, meat and dairy). Yet like a misguided parent giving a kid cotton candy for dinner, state and federal governments get it backwards by giving buckets of cash to animal agriculture while providing almost no help to those raising fruits and vegetables.

7. Big businesses love farm subsidies. Small farmers and rural Americans hate them.

In the last 15 years, two-thirds of American farmers didn’t receive a single penny from direct subsidies worth over $100 billion – the funds mainly went to big corporations. The subsidy money spurs the growth of factory farms, which are surprisingly bad for local economies (they employ fewer workers per animal than regular farms, and they buy most of their supplies outside the local area). That’s why when pollsters asked Iowans how they feel about farm subsidies, a large majority preferred ending the handouts.

8. Factory fishing ships are exploiting the world’s oceans so aggressively that scientists fear the extinction of all commercially fished species within several decades.

Like an armada bent on victory at any cost, the 23,000 factory ships that patrol the world’s oceans have decimated one-third of the planet’s commercially fished species. They also indiscriminately kill and discard 200 million pounds of non-target species, or bycatch, every day. Because of such colossal destruction and waste, the United Nations says fishing operations are “a net economic loss to society.”

9. Fish farming isn’t the answer.

Sometimes hailed as the future of sustainable food production, fish farming is actually just another form of factory farming. Farmed fish live in the same stressful, tight conditions as land animals, and concentrated waste and chemicals from aquaculture damage local ecosystems. Escapes lead to further problems, as in the North Atlantic region where 20% of supposedly wild salmon are actually of farmed origin. When genes from wild and farmed fish mix, it degrades the wild population.

Sometimes hailed as the future of sustainable food production, fish farming is actually just another form of factory farming. Farmed fish live in the same stressful, tight conditions as land animals, and concentrated waste and chemicals from aquaculture damage local ecosystems. Escapes lead to further problems, as in the North Atlantic region where 20% of supposedly wild salmon are actually of farmed origin. When genes from wild and farmed fish mix, it degrades the wild population.

10. If they treated a dog or cat like that, they’d go to jail.

Industry-backed laws passed in the last 30 years make it legal to do almost anything to a farmed animal. Connecticut, for example, in 1996 legalized “maliciously and intentionally maiming, mutilating, torturing, wounding, or killing an animal” – provided it’s done “while following generally accepted agricultural practices.” Since most states have similar exemptions, farmed animals have almost no protection from inhumane treatment.

What’s a person to do?

Vote with your pocketbook. If you’re concerned about the creepy marketing, environmental damage, health risks, economic problems, or ethical issues that plague the meat industry, you can take action immediately. Make a choice to buy less meat, fish, eggs, and dairy – or better yet, give them up completely. It’s one of the most powerful things you can do.

Vote with your pocketbook. If you’re concerned about the creepy marketing, environmental damage, health risks, economic problems, or ethical issues that plague the meat industry, you can take action immediately. Make a choice to buy less meat, fish, eggs, and dairy – or better yet, give them up completely. It’s one of the most powerful things you can do.

For more information and additional solutions, get the book Meatonomics.