Two acres of rain forest are cleared each minute to raise cattle or crops to feed them. 35,000 miles of American rivers are polluted with animal waste. In the mad race to the dinner plate, the scarce resources needed to produce meat, eggs, fish and dairy simply can’t keep pace with the demand for these foods. Some commentators propose “green” alternatives like raising animals locally, organically, on pastures, or in fish farms. But it’s unclear whether these proposals are really viable or are just so much hot, greenhouse gas wafting into the sky.

This is the second installment in a three-part series which seeks to answer the question: can animal foods be produced sustainably? In the first segment, we learned that determining the carbon effects of local consumption can be about as complex as planning a seven-course meal. Simply put, locally raised animal foods can easily be less carbon-friendly than those from a distant continent, and local consumption thus does not make animal foods sustainable. In the third segment, we learn that fish farming may not be silver bullet of food production to feed the world sustainably. In this piece, we look at another key issue: whether farmed animals’ carbon footprint can be improved by raising them organically.

Manic for Organic

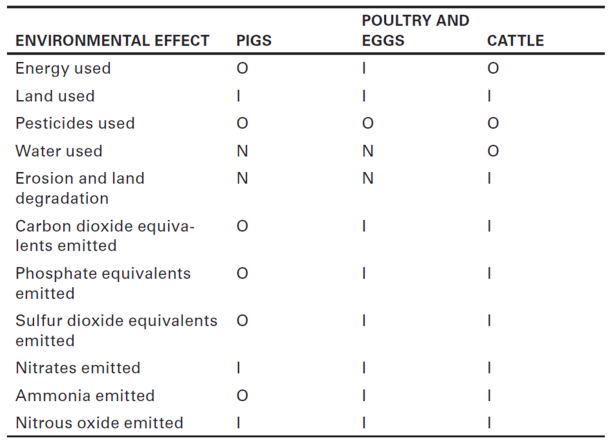

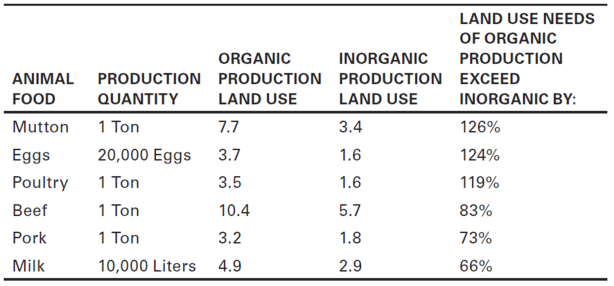

Is organic food really as good for the environment as we’d like to think? Despite Prince Charles’s claim that organic farming provides “major benefits for wildlife and the wider environment,” a 2006 British government report found no evidence that the environmental impact of organic farming is better than that of conventional methods.[1] In fact, because of large differences in land needs and growth characteristics between organic and inorganic animals, it’s hard to draw conclusions about the environmental benefits of one production method over the other. As Table 1 below shows, considerably more land is required to produce organic animal foods than inorganic—in some cases more than double. This higher land use is associated with higher emissions of harmful substances like ammonia, phosphate equivalents, and carbon dioxide equivalents. Further, denied growth-promoting antibiotics, organic animals grow more slowly—which leads to higher energy use for organic poultry and eggs. Thus, as Table 2 shows, when the overall effects of organic and inorganic animal production are compared, the results are notably mixed.

Table 1

Land Use Needs of Organic and Inorganic Animal Food Production (in acres)[2]

Table 2

Organic or Inorganic Production—Which Is Better for the Environment?[3]

Legend:

O = Organic is better (based on lower use or emission)

I = Inorganic is better (based on lower use or emission)

N = No significant difference

We can see that poultry and eggs are mostly more eco-friendly when raised inorganically, while it’s generally more eco-friendly to raise pigs organically. As for cattle, factors like methane emissions and water use make the comparison more complicated.

Take methane. Besides figuring prominently in many a fart joke, it’s a highly potent greenhouse gas (although in its natural state, it’s actually odorless). A single pound of it has the same heat-trapping properties as 21 pounds of carbon dioxide.[4] Organic cattle must be grazed for part of their lives, which means that unlike feedlot cattle, they eat grass. However, cattle rely more on intestinal bacteria when digesting grass than grain, and this makes them more flatulent—and methane-productive—when eating grass. The result is that grass-fed, organic cattle generate four times the methane that grain-fed, inorganic cattle do.[5]

Take methane. Besides figuring prominently in many a fart joke, it’s a highly potent greenhouse gas (although in its natural state, it’s actually odorless). A single pound of it has the same heat-trapping properties as 21 pounds of carbon dioxide.[4] Organic cattle must be grazed for part of their lives, which means that unlike feedlot cattle, they eat grass. However, cattle rely more on intestinal bacteria when digesting grass than grain, and this makes them more flatulent—and methane-productive—when eating grass. The result is that grass-fed, organic cattle generate four times the methane that grain-fed, inorganic cattle do.[5]

Then there are the water issues. On a planet where water is not only the origin of all life but is also the key to its survival, animal agriculture siphons off a hugely disproportionate share of this increasingly scarce resource. It can be hard to picture the quantities of water involved, so consider a few examples. The 4,000 gallons required to produce one hamburger is more than the average native of the Congo uses in a year.[6]

And the 3 million gallons used to raise a single, half-ton beef steer would comfortably float a battleship.[7]

And the 3 million gallons used to raise a single, half-ton beef steer would comfortably float a battleship.[7]

Pound for pound, it takes up to one hundred times more water to produce animal protein than grain protein.[8] Organic cattle require 10 percent less water than inorganic but still need 2.7 million gallons each during their lives, enough to fill 130 residential swimming pools. In light of the orders-of-magnitude difference in water needed to raise plant and animal protein, does a 10 percent savings for organic cattle really matter? Looked at another way, if Fred litters ten times a day while Mary litters only nine times, is Mary’s behavior really good for the environment? The value of such comparisons is dubious.

These factors lead to one conclusion: we must treat as highly suspect the claim that organic animal agriculture is sustainable. Organic methods are an environmentally-mixed bag—sometimes slightly better, sometimes a little worse, and often the same as inorganic. But since animal protein takes many times the energy, water, and land to produce as plant protein, any modest gains from raising animals organically are largely irrelevant.[9] Shocked that organic production isn’t the silver bullet of sustainability? Stay tuned. Next time, we’ll look at another favorite of those who advocate “green” animal agriculture: pasture farming. For more surprising information on this and other issues related to animal food production, check out my just-released book Meatonomics: How the Rigged Economics of Meat and Dairy Make You Consume Too Much – and How to Eat Better, Live Longer, and Spend Smarter (Conari Press, 2013).

[1] C. Foster et al., “Environmental Impacts of Food Production and Consumption: A Report to the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs,” Eldis (2006).

[2] Data expressed in hectares converted to acres. A. G. Williams, E. Audsley, and D. L. Sandars, “Determining the Environmental Burdens and Resource Use in the Production of Agricultural and Horticultural Commodities” (2006), Main Report, UK Department of Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs Research Project IS0205.

[3]Williams, Audsley, and Sandars, “Environmental Burdens in Production of Agricultural Commodities”; David Pimentel and Marcia Pimentel, Food, Energy, and Society, (Niwot, CO: Colorado University Press, 1996).

[4] US Environmental Protection Agency, “Methane: Science” (2010).

[5] L. A. Harper et al., “Direct Measurements of Methane Emissions from Grazing and Feedlot Cattle,” Journal of Animal Science 77, no. 6 (1999): 1392–1401.

[6] ChartsBin, “Total Water Use per Capita by Country,” accessed December 23, 2012, http://chartsbin.com.

[7] Assuming the animal weighs 1,200 pounds; metric units converted to imperial. T. Oki et al., “Virtual Water Trade to Japan and in the World” (presentation, International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade, Netherlands, 2003).

[8] Pimentel and Pimentel, Food, Energy and Society.

[9] David Pimentel and Marcia Pimentel, “Sustainability of Meat-Based and Plant-Based Diets and the Environment,” American Clinical Journal of Nutrition 78, no. (3) (2003): 6605–-35.

Glad you point this out Dave. Most organic is done as monoculture under artificial conditions – think Salinas Valley lettuce in summer. Only smallholders approximate Neolithic ag in balance with the biome such as planting a diversity or crops that work well together with the local soil, moving fields, etc. And corporate America is going organic –at least in some subsidiaries — in an effort to control costs through extractive and unsustainable ag methods while selling organic at a higher demand elasticity price point.

Would love to see more on this and how smallholders can reconnect with the market by refocusing purchasing preferences away from artificially cheap food to sustainable food.

Thanks John – yes I think in this case the “organic” war cry is little more than an attempt at rationalizing a number of destructive, industrial farming methods.

I see why there are only 2 comments on such a controversial subject; all the dissenting views, like my former post, are deleted. Ah, brilliant debating technique.

Organic foods done right yield at least equal amounts per acre to chemical industrial agriculture. That’s even more true when the land required for the fossil fuels and mined phosphate rock etc. required for chemical fertilizers are included. Of course it must be. Is it ever?

Even more striking, permaculture guilds like the 3 sisters can yield 20% more than chemical monocultures, according to Jane Mt. Pleasant of Cornell U. And edible forest gardens promise even greater productivity.

Saying “locally raised animal foods can easily be less carbon-friendly than those from a distant continent,” really means very little. If it “can…be” it means it can be otherwise, as well, that is, locally raised meat can easily be lower, even much lower in carbon emissions than distantly raised meat. And of course that’s intuitively obvious. All other things being equal—and there’s no reason to believe they’re not equal—raising animals and then shipping them or their carcasses thousands of miles might be exactly what it seems: an incredibly wasteful and stupid practice temporarily enabled by a bizarre and insane warped economic system, rife with inequity and encouraging that so it can siphon off a substantial profit at every step.

But all of that is besides the point if we really want to make a difference. The article raises t question—to me—of local vs vegetarian issue, and to put it simply, you can be local all week or vegetarian or vegan for a day and have the same carbon-reduction effect. Come back with facts and refs about veg. being better; that meat can’t be produced in US/person amounts sustainably no matter how it’s done. Doing it for even such a small % as we are is wrecking the planet, causing as much as half of human-caused ghgs.

Thanks for your comments. Your earlier post was not deleted, it was simply never approved because it lacked support and was overly argumentative in tone (you referred to work supported by citations as “nonsense,” which is not productive).

In fact, this blog post is merely a series of small summaries or extracts from my book Meatonomics, which is supported by more than 700 endnotes. I recommend you get the book and read the chapter on “The Sustainability Challenge” associated with animal foods. For your convenience, an excerpt posted at http://wp.me/a3EufG-7r contains some of the discussion and sources.

To the extent you can provide support for the idea that all organically farmed animals can be raised on the same amount of land as inorganically farmed, I’d be interested.

I already did supply support for the argument: Jane Mt. Pleasant of Cornell. Yields 20% higher than chemical monocultures. Since more food can be grown with organic permaculture on any given amount of land than can be grown as chemically monocropped food, and livestock get fed food, it seems logical to suppose that livestock can be grown organically without using more land, and using permaculture, can be grown using fewer resources of all kinds–fertilizers, pesticides, land used for mining fertilizers, natural gas used for nitrogen…

But none of that is the point. However it’s grown meat is a vastly less efficient use of precious resources than plant foods are. Land, water, energy, labor… every resource one can think of, large amounts would be saved by eating less or no meat.

PS. Deleted vs. never approved: a distinction without a difference.

Interesting comments and debate. I’d love to chime in. I think as long as we live in communities and rely on corporate – profit oriented farms, be they organic or not, we are going to remain dependent upon The Man and reek havoc on our health and the health of the Planet.

The task is huge.

Somehow we need to ban together in our communities, dump the educational systems designed to prepare our children for slavery to a machine state; entice the development of wholesome foods that are raised sustainably in that they take into accounty not only human health, but planetary health, etc.

There are groups out there…permaculture, transition towns, etc that put people into contact with others who are into self-sustaining, self-empowering practices that are healthy for people and planet. My wife and I are trying to home in on this somewhat silent movement with our on-line radio show, “Envision This!”

Be it in industrial farming, industrial organic farming, education and the overall work place: our model is that of standardizaation under a strict top-down rule. However, as Chaos Theory and Holographic Theory of biology and physics states, everything effects everything else. Thus, your breathing as an impact on the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere in relationship to the trees, plants etc on this Earth in terms of the contents of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

It is with this in mind that we should make our decisions instead of surrendering our power to the corporate and governmental sociopaths. This is not an old mind-set. Native American tribes sued to make decisions based on an imagined impact on 7 generations to the future. Hell, long-term planning at best for us is 5 years and generally its in terms of how much money (an artificial construct) we can raise in a short period of time.

“To hell with future generations” is our call…and is going to become our undoing.

Reblogged this on A life of quality! and commented:

Another interesting post from the fine folks at Meatonomics…

Engaging from start all the way through to the end of the comments! I’m not particularly learned so can’t add much, but I’m impressed by the number of footnotes which support your book. Cheers.

[…] article originally appeared at meatonomics.com under the title, Can Animal Foods Be Produced Sustainably? (Part Two: Organic Follies) and is reprinted with the author’s […]

An interesting article to say the least, having not had a chance to vet over the sources cited I have to ask, does the information used to come to your conclusion take into account the environmental benefits of reduced pesticide and chemical use? Further more, is the article written in the context of large scale ‘industrial’ production or local, decentralised production? It does not seem to consider that while the growth phase may produce more emissions, reductions in the emissions from transportation and processing stages that provide benefits?? Further to this, the manure that is produced in organic farming can be utilised within local farms as natural fertiliser – providing an additional benefit…